A personal story of what impacts us all

By Kenneth Ingraham, current president of AIPP

Editor’s note: This story was originally shared by Ken verbally during the introduction to AIPP’s Town Hall in November, 2024, and is adapted here for written clarity.

Let me tell you about how I got into this mess. When I met Jeff Wirth 20 years ago, he was in the middle of producing an experience in conjunction with UCF’s stage production of God’s Country, a play by Steven Dietz about the white supremacist militia movement of the late 1980s. It’s the story of how hatred led to the murder of journalist Alan Berg. It’s heavy material, and certainly not meant to coddle the audience.

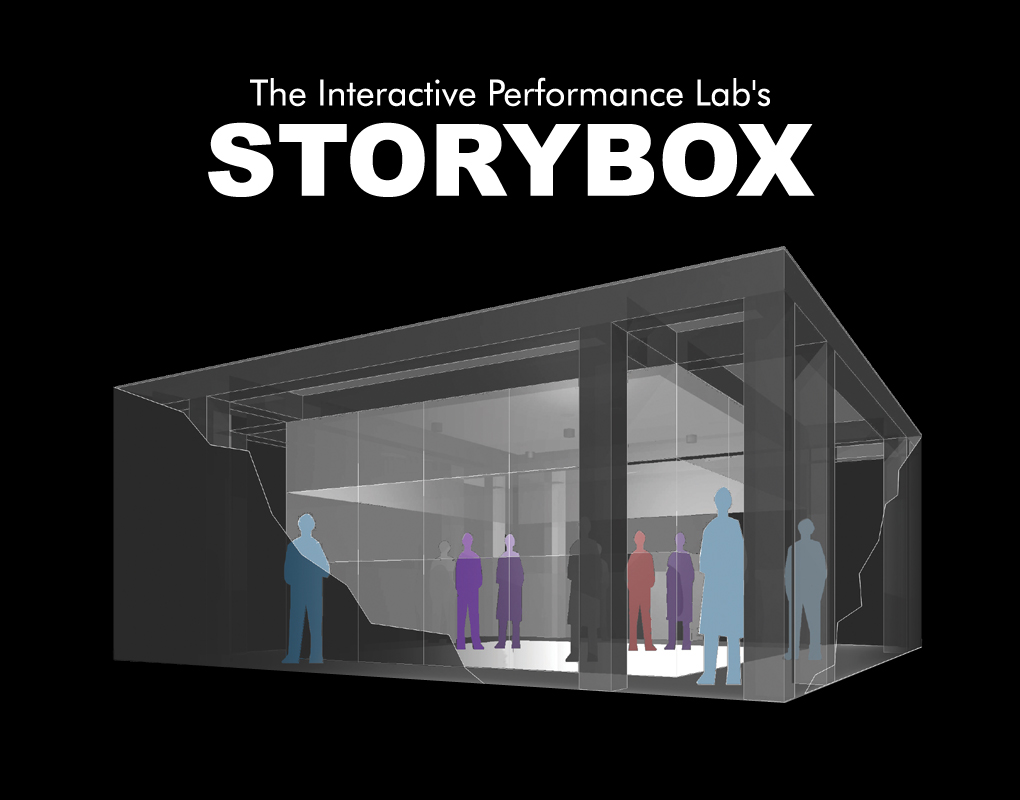

Jeff was directing a team of interactors in the StoryBox, which is like a live-action holodeck. It’s a four wall black box in which interactors—actors who guide interactions—enter through plain curtains and improvise a story experience with spect-actors—people without a script or preparation who are invited into an Interactive Performance as the main character and around whom the story evolves based upon their own contribution and choices. The minimalist design of StoryBox allows the spect-actor to experience almost anything because the story takes place solely through interpersonal interactions. Scenes shift dynamically and a story can encompass many years of characters’ lives, all in the contained space and within 15 minutes.

The goal of this particular production was to give the audience a chance to live inside the world of these white supremacist militias. The subject matter was made clear in advance. The purpose, which wasn’t explicitly mentioned ahead of time, was to give them an insight into how someone could be lulled into a cult before they realize it, simply because they are surrounded by family and friends who make them feel accepted and loved. It’s an admittedly recognizable phenomenon, but the StoryBox delivered it in a way that felt very personal because of the immersive nature, but also because of the skills of the interactors.

This wasn’t the blue-sky story crafting typical for StoryBox where spect-actors enter and could end up being anything from a president to a rockstar to the parent of a sick child. No, the God’s Country StoryBox Experience was based on a specific scenario written to establish the

spect-actor’s backstory and present them with a critical life emergency that they were helped through by friendly, like-minded people who welcomed them into their community. Relationships formed, care was provided, and loyalty was established, and every now and then there would be peppered into the story mention of outsiders who weren’t so nice, people that threatened the spect-actor’s character. But this mention was subtle, and could easily be dismissed as the legitimate fault of those outsiders.

One critical aspect was that the spect-actor’s character was treated as being White. This happened no matter the racial makeup of the spect-actor in real life. It was blind casting for the interactors too, so people regardless of their complexion were endowed with a set racial identity in the story.

Then these stories would end with a reveal, in a very O. Henry or Twilight Zone style. Perhaps the community would all gather to pose for a photo and then raise their arms in a Hitler salute. Or the action would lead to a culminating final scene in which interactor characters would reveal that the reason for their isolation was to reject or even attack people who were Jewish, or Black, or Latino, or Asian. At this pivotal moment, the lights would go out and the spect-actor was left to ponder what just happened.

Sounds a bit like a psychological crime, right? An assault on people’s well-being. A deliberate manipulation of someone’s inherent morals and belief in their own principles. And that story melodrama really did seem to be the point, and what people remember from it. After all, it’s the juicy bit. But the full experience never ended like that. The curtain moment, no matter how powerful, was not the end of StoryBox for anyone who entered. Because this was not a propaganda tool. The goal was neither to simply shock people with the horror of Nazism, nor was it an apologetic for racism.

Because as soon as the spect-actor left the StoryBox, they were brought into the talk-back. The talk back was generally in a circle with Jeff, the director, all of the cast of interactors, and the spect-actor. It always started with a chance for the spect-actor to reflect on what they’d experienced and express any thoughts they had about the experience.

Jeff made sure to treat the person with the utmost respect and care. Often the spect-actor would have many questions about how it all worked, and these questions were answered thoughtfully. The team of interactors were very well trained and aware of what the experience could bring out in spect-actors, and also what their own contribution to the talk-back could do to shape the spect-actor’s experience. They made sure not to lead the spect-actor in questions. It was explicit that the interactors were not their characters, just as the spect-actor was not the character they played. In this way, everything that happened in StoryBox stayed in StoryBox, and it was left to the spect-actor to decide (or keep private) how much of themselves they brought to the character.

This separation of characters, and the emphasis on the freedom of the fiction was absolutely essential. No StoryBox experience happened without it. And it was often in these talk-backs that the most significant moments happened.

One story that sticks with us is about a young college-aged man. He is African American, so the blind casting was obvious in that he was endowed as being a White man in this story about white supremacy. As the story began he didn’t know where the story would lead but his character was accepted into the racist community as if he were just like them. At some point in the experience he realized that he was playing a white father whose daughter was getting married, and it ended with a salute of people as he walked her down the aisle. During this man’s talk-back he didn’t express his feelings but said he would have to think long and hard about the experience. Everyone on the team was worried.

Some time later, he wrote Jeff a letter in which he described his feelings. He is tall, and he always knew that being tall and Black and male made him stand out, and often in uncomfortable ways. He described how he tried to shrink himself in real life social situations so that he wouldn’t be seen as “intimidating”. But in the StoryBox, he was being deferred to by white characters. He wrote how he wasn’t used to that, and that he didn’t feel the need to shrink himself in the StoryBox. And he said he appreciated the chance to be who he was naturally – meaning standing to his full height without apology – even though he literally was playing someone he wasn’t, and that he still rejected the racist reason within the story for why he had that power.

And, critically, he was not going to defer to people because of skin color.

Now, let’s talk about the inherent dangers of this. Was there manipulation? Was it a gotcha prank being played on spect-actors? Was there the chance for spect-actors to abuse this situation? Could the interactors abuse spect-actors? Could interactors, after spending weeks marinating in racial hatred come out the other side with the effects of trauma? The answer to all of these is yes, it’s possible. Did this man I’ve described walk away powerfully impacted? Was the subject matter upsetting to him? Apparently, but also in another way, empowering.

How do we prevent those awful outcomes while leaving room for the transformative ones? I suggest that the first step is to announce to ourselves and our productions that the potential for harm exists. To deny it would be naïve, dishonest, and downright unprofessional. We literally can’t engage in interactive performance if we tell spect-actors exactly what is going to happen, because there’s no way to know how it will play out. If we did, it wouldn’t be interactive performance. And they might as well watch a stage play or film. And we wouldn’t be able to deliver experiences like God’s Country StoryBox without accepting these risks.

So there’s the challenge. And it’s not my role to provide answers. It’s all of ours as a community of creators. We are the people who must grapple with this daily. It’s on us to build in safeguards that respect the work, and also the people doing it and our spect-actors. We need a contingency plan, and not keep those plans in black books that we only pull out and tell everyone what to do if something goes horribly wrong. We can’t run our productions without mentioning the elephant in the room. We need everyone to understand the potential, how to recognize it if it occurs, and what to do in the situation.

This is how you make things not that suck all the fun out, but things where your team of people are empowered to make it the best it can be. Best practices of stage management and film production can get us a long way there, and I encourage you to adopt such processes where appropriate. There’s no reason to be reinventing the wheel at every stage. And I encourage you not to rest on siloed thinking, as if only certain people who bear the responsibility in their job title are supposed to think about what can happen.

If we’re going to improvise as a production, we need training. A stunt person doesn’t do a high fall without preparation and gear. And in an Interactive Performance, the roles are not nearly as clearly defined or limited. Many times a camera person ends up being accosted by a spect-actor and they have to play it off as part of the story. An interactor may need to catch a spect-actor who slips on a spilled drink, and unsuspecting drunk members of the public interrupt scenes when they play out on city streets. Having a performance and production team that is

completely versed in psychological and physical safety as it pertains to the project is better equipped to safeguard the spect-actor and everyone else.

No, you probably can’t plan for every outcome, but you can arm your people with the tools to deal with things as they happen in a way that respects everyone. I invite you to explore, and ask, and to share. That’s what the AIPP is here for.

About the author:

Kenneth Ingraham is proud to be a co-founder and to serve as the first president of the AIPP. In addition to working as an Inter-actor for over a decade, he pioneered the production of many forms of Interactive Performance. Over his varied career, he has produced interactive performance projects for Walt Disney Imagineering as well as showcase events at the Florida Film Festival and South By Southwest. His company, Interactor Simulation Systems, provides simulation, training, and consulting services utilizing Inter-Actors in the Orlando area. Kenneth’s interests include race car driving and playing the cello.